It’s that period of the year already ! With December comes the Advent of Code programming challenge, and its daily mental workout.

Advent of Code is an Advent calendar of small programming puzzles for a variety of skill sets and skill levels that can be solved in any programming language you like.

The complexity level of the programming challenges increase every day, and tend to be notoriously hard during the last few days. However, as of writing this article, it’s only day 9, and there were a few problems that didn’t require too much processing cycles, provided you spent enough mathematical effort and didn’t come up with only the brute-force solution.

Therefore, in order to gain more experience with the buzzing eBPF technology (#🐝), I challenged myself to try and solve some of the AoC challenges with eBPF. This obviously cannot be recommended, and is not where eBPF will shine the most, but solving the AoC challenges with exotic programming languages (and architectures) is a thing, as it appears! Some examples include: “one language a day” solutions, Turing Complete assembly simulator, writing the solutions in assembly, and even using a quantum computing algorithm.

AoC - Day 6th

The 6th day of the 2023rd Advent of Code describes boat races, and asks to find in how many ways a race can be solved, given a race duration and the previous record/distance (that you must exceed). The rules of the fictitious (and physically impossible) challenge are as follows:

at the beginning of the race, you hold a button for \(\mathrm{hold}\) milliseconds, and your speed will be equal to your holding time.

The race then goes on for another \(\mathrm{duration} - \mathrm{hold}\) milliseconds, and you final distance is given by \((\mathrm{duration} - \mathrm{hold}) * \mathrm{hold}\).

As we have to find the minimum and maximum \(\mathrm{hold}\) that permit us to beat the previous record, we can formulate the problem as finding the solutions to:

$$-\mathrm{hold}^2 +\mathrm{hold}*\mathrm{duration} - \mathrm{record} = 0$$

In other terms, solving the challenge amounts to solving the above quadratic expression, which we can do using the quadratic formula:

$$x = \frac{ -b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} \text{ , with } ax^2 + bx + c = 0$$

In our case, we have \(x = \mathrm{hold}\), \(a=-1\), \(b = \mathrm{duration}\), and \(c = \mathrm{record}\).

Note that in our personalized input for the challenge, we are given multiple races, and for each race we need to find the minimum and maximum \(\mathrm{hold}\) time to win the race, and then compute the difference of those value to know in how many ways we can win each race.

Here comes eBPF

While solving the above equation would be trivial with a “normal” programming language (i.e. with floating point arithmetics, and access to basic math libraries), doing the same with eBPF will prove more challenging. Indeed, we will only be able to work with integer, and we will need to implement a square root algorithm, all of which should satisfy the infamous eBPF verifier, which make our life much harder through making sure that we e.g. do not introduce infinite loops or invalid accesses to the memory.

Where to start ?

The first question: how/where do I actually run/execute an eBPF program? Quoting https://ebpf.io/what-is-ebpf/#hook-overview:

eBPF programs are event-driven and are run when the kernel or an application passes a certain hook point. Pre-defined hooks include system calls, function entry/exit, kernel tracepoints, network events, and several others.

For this example, I chose to attach the eBPF program to the predefined tracepoint/syscalls/sys_enter_openat hook point, which means our eBPF program will be run whenever a file is opened on our machine (and to prevent actually running the program all the time, I only run the actual program when the filename arg corresponds to a predefined path).

Knowing this, the next few questions will be: how do I write the eBPF program, how do I load it ? And how can I communicate with it ?

For answers to these questions, I recommend reading eBPF.io “Introduction document” and the the eBPF Go library “Getting Started” guide.

In a few words, we will write the eBPF program in C, compile it with clang, then the ebpf-go library will generate Go skeletons to load and work with the actual eBPF program, and finally a Go application will be loading the eBPF program and communicating with its maps, allowing us to send the input to the challenge and to retrieve the result, once it will have been computed.

eBPF code

Exchanging data between Go code and eBPF

First of all, to exchange data between the Go application (that loads the eBPF program into the kernel) and the eBPF program, we will use a simple map (of type array), with the following definition:

struct

{

__uint(type, BPF_MAP_TYPE_ARRAY);

__type(key, __u32);

__type(value, __u64);

__uint(max_entries, 10);

} aoc_map SEC(".maps")

This will be a map named aoc_map, mapping __u32 keys to __u64 values, and containing at most 10 entries.

The first entry will contain the count of races to process, the next count entries will contain the duration (in the leftmost 32 bits) and the record (in the last 32bits) of each race, and the following 2 entries will contain the result of day 6th challenge respectively for part 1 and part 2.

The first count + 1 entries of the map are set in the Go application with the following Go code:

// inputBytes:

// Time: 62 73 75 65

// Distance: 644 1023 1240 1023

spl := strings.Split(string(inputBytes), "\n")

duration := regexp.MustCompile(`\d+`).FindAllString(spl[0], -1)

record := regexp.MustCompile(`\d+`).FindAllString(spl[1], -1)

var aocKey uint32 = 0

_ = objs.AocMap.Update(aocKey, uint64(len(duration)), ebpf.UpdateAny) // set the 0-th map value to the count

for i := 0; i < len(duration); i++ {

dur, _ := strconv.ParseUint(duration[i], 10, 64)

rec, _ := strconv.ParseUint(record[i], 10, 64)

aocKey++

_ = objs.AocMap.Update(aocKey, dur<<32|rec, ebpf.UpdateAny) // set the 0-th map value to the count

}

In the eBPF code, the input values are retrieved as follows:

for (__u32 i = 0; i < *count && i < sizeof(aoc_map.max_entries); i++)

{

key++;

__u64 *dur_rec = bpf_map_lookup_elem(&aoc_map, &key);

if (!dur_rec){return 0;} // if the pointer is NULL, the map isn't ready yet

__u64 tuple = *dur_rec;

__u64 duration = tuple >> 32;

__u64 record = tuple & (((__u64)1 << 32) - 1);

bpf_printk("duration: %8d record: %8d", duration, record);

}

Solving the challenge

Now that we have the \(\mathrm{duration}\) and \(\mathrm{record}\) parameters in the eBPF program, it is time to compute the root of the quadratic polynomial expressed above.

Due to the nature of eBPF however, this will be tricky, as we can neither use float nor the math.h library, which means we will have to cope with ceil or floor issues with some tricks, and we will have to implement a square root algorithm by ourselves.

sqrt in eBPF

To compute the square root of an integer, we take inspiration of Wikipedia’s article over “Integer square root” and implement Newton’s (/Heron’s) algorithm as follows:

// Square root of integer

__u64 int_sqrt(__u64 s)

{

// Zero yields zero

// One yields one

if (s <= 1)

return s;

// Initial estimate (must be too high)

__u64 x0 = s / 2;

// Update

__u64 x1 = (x0 + s / x0) / 2;

__u32 safeguard = 0; // prevent infinite loops

while (x1 < x0 && safeguard < 300)

{

x0 = x1;

x1 = (x0 + s / x0) / 2;

safeguard++;

}

return x0;

}

The only minor modifications w.r.t. the Wikipedia example are the precise type definition for all variables, and a safeguard variable, which prevents our while loop from looping over indefinitely.

Indeed, any eBPF program is first verified by the eBPF verifier before actually being loaded into the kernel, and without the safeguard < 300 condition, the verifier will refuse loading the program, with an error message similar as this:

argument list too long: ; while (x1 < x0) // prevent infinite loops: 222: (2d) if r9 > r2 goto pc-6 ....

Computing the roots

Now that we have our int_sqrt function, we can try to compute the min/max holding time for our equation. Doing so without floats is a bit cumbersome, because we want our minimum holding time to be strictly greater than the real \(h_{min} \) solution (i.e. we want the ceil() of the \(h_{min} \) root), and we want our maximum holding time to be the floor() of our \(h_{max}\) solution.

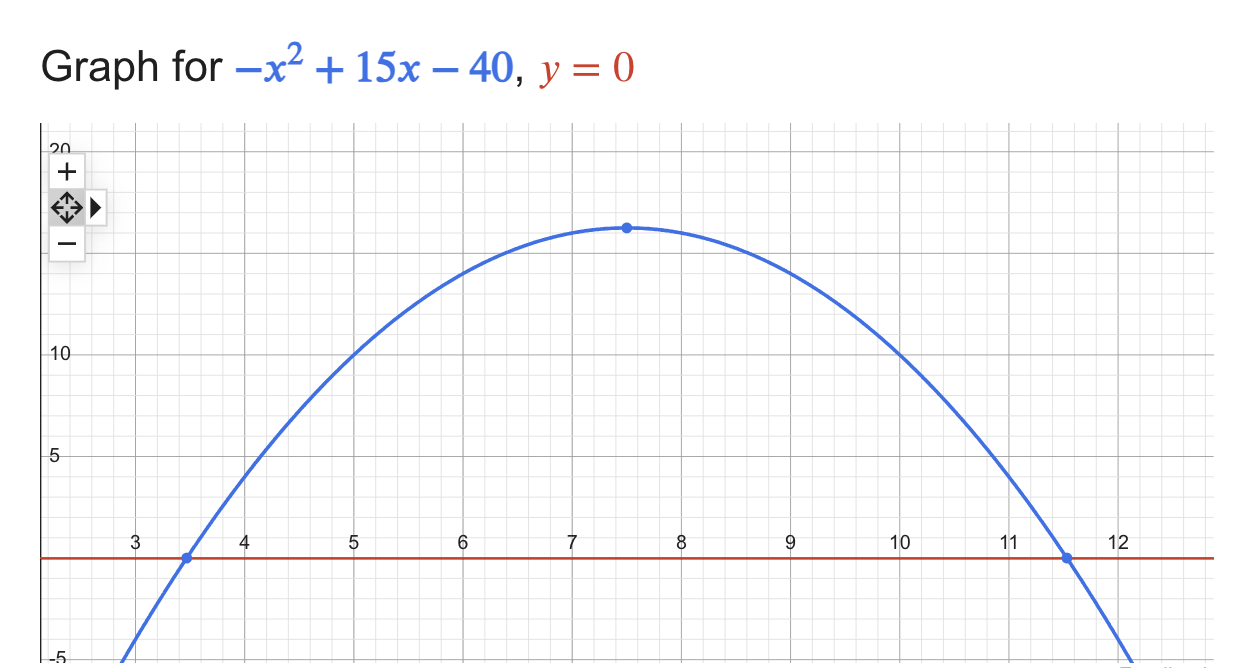

To better understand why, we can have a look at the graph of our equation when the race duration is 15s and the record is 40m.

That is, we will only ever beat the record if the holding time is in the [4,10] interval, that is, if \(h_{min} = \lceil 3.469 \rceil = 4\) and \(h_{max} = \lfloor 11.531 \rfloor = 11\)

Computing ceil and floor of integers is not trivial however 😅.

The floor case is given thanks to rounding errors during e.g. divisions (although it might need additional precautions, but in the examples I had to work with, it was never an issue).

Computing ceil is more involved, but one way to solve the problem is to multiply all parameters by 100 and to verify whether the remainder of the result modulo 100 is greater than 0: if that’s the case, you can increase the result by 1.

(while this trick worked correctly in my examples, it might be needed to use more precision by increasing the precision multiplier).

The eBPF code to implement quadratic roots looks as follows:

__u64 compute_ways(__u64 duration, __u64 record)

{

record += 1; // we must be strictly greater than the last record

__u64 h_min, h_max;

__u64 h_min_100 = (100 * duration - int_sqrt(10000 * (duration * duration - 4 * record)))/2;

if (h_min_100 % 100 > 0) // manually implement the ceiling function

{

h_min = h_min_100 / 100 + 1;

}

else

{

h_min = h_min_100 / 100;

}

h_max = (duration + int_sqrt(duration * duration - 4 * record)) / 2 + 1;

bpf_printk("h_min: %8d h_max: %8d", h_min, h_max);

return h_max - h_min;

}

Solutions for part 1 & 2 of the challenge

Solving the 1st part of the challenge amounts to using our compute_ways function for all duration and record pairs, and to multiply all those results together. Nothing too complicated so far 🙃

However, all Advent of Codes challenges consist of 2 parts, the second one being a modulation (often constructed as a blocker for brute-force solutions) of the input for the first part. For this challenge, the second part consists in appending all base-10 represented digits together for both the duration and the record. More concretely:

// part1 (4 races):

// Time: 62 73 75 65

// Distance: 644 1023 1240 1023

// part 2 (1 race):

// Time: 62737565

// Distance: 644102312401023

We construct dur2 and rec2 integers iteratively while processing the races of part 1, with the following code:

// parse part2 number

__u64 sfgrd = 0, tmp = duration;

while (tmp > 0 && sfgrd++ < 10)

{

dur2 *= 10;

tmp /= 10;

}

dur2 += duration;

sfgrd = 0;

tmp = record;

while (tmp > 0 && sfgrd++ < 10)

{

rec2 *= 10;

tmp /= 10;

}

rec2 += record;

Finally, we can reuse the compute_ways function defined earlier to compute the solution to part 2.

Because dur2 and rec2 are much larger than before however, I needed to increase the maximum number of iterations in the int_sqrt function, as it didn’t have time to converge otherwise.

Printing the solution(s)

Now that we have computer the results for both part 1 & 2, we are only left with finding a way to print those results outside the eBPF program. The fastest and most efficient solution is, as described above, to use the following next 2 entries of our aoc_map to exchange data between the Go application and the eBPF program.

It is however also possible to print debug message from within the eBPF program, using the bpf_printk(fmt,args...) helper macro. Such debug messages will then be printed out to /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe.

Conclusion

The main Go file as well as the eBPF program code can be inspected on my advent_of_code GitHub repository.

For info, I’ve developed and run my code on a Mac M2, within a Lima VM, and was quite pleased with the overall experience. Although challenging, developing eBPF code is interesting and an excellent mental workout! Hopefully I’ll have more occasion to write eBPF code in the future. For another Advent of Code Challenge already maybe ?

Finally, I’ll leave the last few words of this blog post to the stdout of this project, which should speak for itself 🙃

root@lima-ebpf-lima-vm:/tmp/lima/aoc06# uname -a

Linux lima-ebpf-lima-vm 6.1.0-13-cloud-arm64 #1 SMP Debian 6.1.55-1 (2023-09-29) aarch64 GNU/Linux

root@lima-ebpf-lima-vm:/tmp/lima/aoc06# ./aoc06

2023/12/09 15:48:10 Starting Advent Of Code - day 06 - eBPF solution

Loading the eBPF objects into the kernel

Updating the eBPF map with the race parameters (the input)

Attaching the eBPF program to the sys_enter_openat tracepoint

triggering the eBPF program

res1 393120 res2 36872656

Debug info (/sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe):

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909665: bpf_trace_printk: duration: 62 record: 644

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909728: bpf_trace_printk: h_min: 14 h_max: 49

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909728: bpf_trace_printk: duration: 73 record: 1023

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909729: bpf_trace_printk: h_min: 19 h_max: 55

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909729: bpf_trace_printk: duration: 75 record: 1240

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909729: bpf_trace_printk: h_min: 25 h_max: 51

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909729: bpf_trace_printk: duration: 65 record: 1023

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909730: bpf_trace_printk: h_min: 27 h_max: 39

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909730: bpf_trace_printk: dur2: 62737565 rec2: 644102312401023

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909731: bpf_trace_printk: h_min: 12932455 h_max: 49805111

aoc06-192981 [001] d...1 167443.909731: bpf_trace_printk: res1: 393120 res2: 36872656